Intro

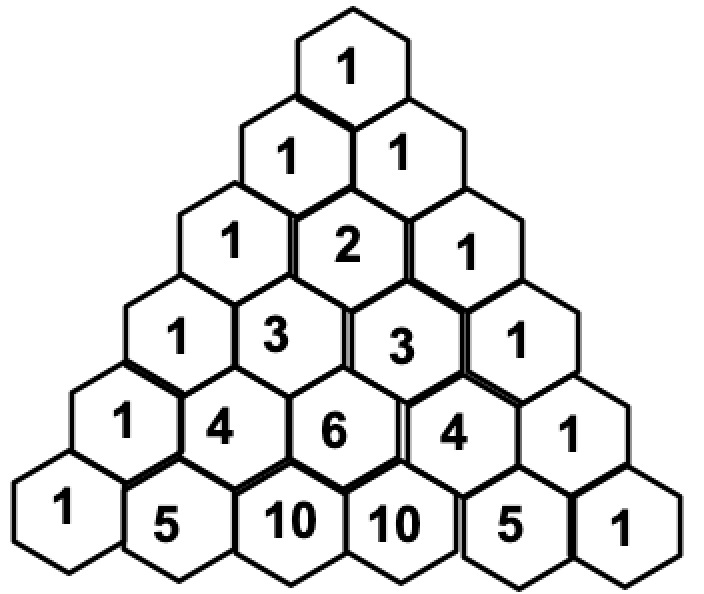

You have probably encountered the Pascal’s triangle - a triangle 1formed by repeated adding the two values above it.2

The Pascal’s triangle has lots of nice properties. We might wonder what a three-dimensional Pascal’s triangular pyramid looks like, and what properties of the Pascal’s triangle translate. It turns out, most of them do; and there’s some beauty in the new symmetries we find.

Recommended Background

Only an interest in math. I’ll cover the basic properties of Pascal’s triangle.

Pascal’s Triangle

Before talking about multiple dimensions, let’s talk about the two-dimensional case. This long section can be skipped if you have good familiarity with Pascal’s triangle. The slow treatment of well-known properties is meant to motivate claims we will make about higher dimensional Pascal simplices.

You can construct the Pascal’s triangle term-by-term by simply adding the two numbers above it.

1

1 1

1 2 1

1 3 3 1

1 4 6 4 1

1 5 10 10 5 1

1 6 15 20 15 6 1

1 7 21 35 35 21 7 1You can view the outside edges as always being 1 as a rule, but I like to view them as being the sum of 1 with an unwritten zero on the other side.

In this way the Pascal’s triangle lives on an infinite lattice in all directions, with lots of zeros. The summation rule is enforced even on the zeroes, because 0=0+0. Then there’s just a single cell, the top of Pascal’s triangle that doesn’t obey the summation rule, because it’s not the sum of the two zeroes above it. And like the big bang, it then populates all the non-zero terms you see.

The first property of Pascal’s triangle that I want to talk about is that the sum of each row is double the sum of the row above it. If we call the top row (with the single cell) the 0th row, the next one the 1st row, and so on, we have the property that the n-th row terms add to 2^n.

This is because every cell in one row gets added to exactly two terms in the row below it. Look at the transition between the 4th and 5th row:

1 4 6 4 1

1 5 10 10 5 1This can be written as

1 4 6 4 1

1 1+4 4+6 6+4 4+1 1Every term from the 4th row showed up exactly twice in the 5th row. So of course the sum will be double.

The second property I want to talk about is that the terms represent the number of rearrangements. To see what I mean, let’s say we have four blue or red balls, and I want to know how many ways I can rearrange them. We assume all red balls are identical, so if I switch two of them that wouldn’t be a new arrangement.

If I have 4 blue and 0 red, then there is 1 arrangement: BBBB

3 blue, 1 red, then 4 arrangements: RBBB, BRBB, BBRB, BBBR

2 blue, 2 red, then 6 arrangements: RRBB, RBRB, RBBR, BRRB, BRBR, BBRR

1 blue, 3 red, then 4 arrangements: RRRB, RRBR, RBRR, BRRR

0 blue, 4 red, then 1 arrangement: RRRR

Notice that the numbers 1, 4, 6, 4, 1 are exactly the 4th row of the Pascal’s triangle.

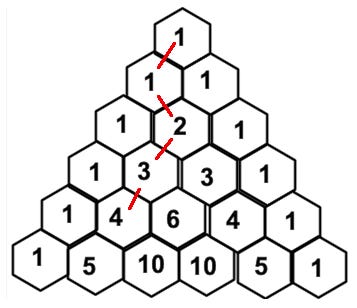

This is no coincidence. Start at the top and work your way down to the first 4 on the 4th row. Working your way down means going left or right with each new row.

As you descend, write down whether you went left or right. In the image above, we went LRLL. You’ll see that in order to end up on that four, you have to had gone left 3 times and right 1 time. And 4 is the number of different ways to go left 3 times and right 1 time. I’ve made a connection, but I haven’t argued yet why 4 should be the number in that cell.

The rough idea is that every number in the triangle is ultimately a sum of 1s

4 = 1 + 3

= 1 + (1 + 2)

= 1 + (1 + (1 + 1)As you trace where each of these 1s come from, you will trace out all possible turns left and right that led you to the 4.

Some readers might benefit from a more formal proof by induction. Call “nCr” the number of ways you can arrange n into r left turns and (n-r) right turns. I claim that nCr is the r-th cell of the n-th row. Obviously 1C0 = 1C1 = 1, so the cells in the first row equal nCr. Now if you have r left turns and (n-r) right turns, then either you turned left at the last step and there are (n-1)C(r-1) ways to arrange the other terms, or you turned right at the last step, and there are (n-1)Cr ways to arrange the other terms. So nCr = (n-1)C(r-1) + (n-1)Cr; this is the total number of ways to arrange n left turns and (n-r) right turns. But this is the sum of the two cells above the r-th cell of the n-th row, so the induction step holds.

If you replace left turns with blue balls and right turns with red balls, then you can see how the Pascal’s triangle holds numbers of rearrangements.

These numbers have all kinds of applications. We could replace ball with cards or letters to get number of ways to draw 3 kings and 2 queens or the number of ways to rearrange the letters of the word “naan”.

One such application is the number of ways to arrange variables in a binomial expansion:

(x+y)^3 = (x+y)(x+y)(x+y)

= x(x+y)(x+y) + y(x+y)(x+y)

= xx(x+y) + xy(x+y) + yx(x+y) + yy(x+y)

= xxx + xxy + xyx + xyy + yxx + yxy + yyx + yyy

= x^3 + 3x^2y + 3xy^2 + y^3The last step combines like terms. But we can see from the calculation that, for example, the number of x^2y terms are the number of different ways we can rearrange two x’s and 1 y.

Generalizing this allows us to look at the Pascal’s triangle for a quick way to calculate arbitrarily large expansions:

(x+y)^5 = 1x^5 + 5x^4y + 10x^3y^2 + 10x^2y^3 + 5xy^4 + 1y^5Plugging in x=y=1, we again see that the sum of rows are powers of two:

(1+1)^5 = 1+5+10+10+5+1We write these terms nCr like:

They have a nice formula. Consider the number of ways to arrange n distinct objects generally. Consider for example, ABCD. You have n choices for the first object. But for the second object, you only have (n-1) choices, because you already picked the first object. For the third object, you have only (n-2) choices and so on. The number of ways you can arrange these objects has to consider each possibility multiplied:

We can check that ABCD has 4!=24 rearrangements:

ABCD, ABDC, ACBD, ACDB, ADBC, ADCB,

BACD, BADC, BCAD, BCDA, BDAC, BDCA,

CABD, CADB, CBAD, CBDA, CDAB, CDBA,

DABC, DACB, DBAC, DBCA, DCAB, DCBAWhat’s different about our situation is that the objects are not distinct. Imagine instead of ABCD, I have ABCA. If I list the 24 arrangements, I’ll see I’ve counted the same arrangements multiple times.

ABCA, ABAC, ACBA, ACAB, AABC, AACB,

BACA, BAAC, BCAA, BCAA, BAAC, BACA,

CABA, CAAB, CBAA, CBAA, CAAB, CABA,

AABC, AACB, ABAC, ABCA, ACAB, ACBAIf you look carefully, you’ll see that every arrangement shows up exactly twice. This isn’t a coincidence. This is because every sequence, like ACAB, represents two ways we originally arranged A and D: ACDB and DCAB. If instead of the A repeating twice, it repeated three times (say ABAA), I’d have over-counted by a factor of six. Every sequence, AABA, represents the six ways I can arrange the 3 As: 12B3, 13B2, 21B3, 23B1, 31B2, 32B1.

Generally if I have r As and (n-r) Bs. I could count the number of ways to arrange n disticint objects n!, but I would have overcounted by a factor of r! for all the ways I could rearrange the As and by a factor of (n-r)! for all the ways I could rearrange Bs. Giving the formula:

I’ll give one more example. 4C2 = 6. This is the number of ways I can arrange 2 As and 2 Bs. I’ll show these as A/a and B/b, you can understand that these are actually the same.

ABab, ABba, AaBb, AabB, AbBa, AbaB,

BAab, BAba, BaAb, BabA, BbAa, BbaA,

aABb, aAbB, aBAb, aBbA, abAB, abBA,

bABa, bAaB, bBAa, bBaA, baAB, baBAThere are the same 24 terms, but everywhere that A comes before a, the same sequence shows up with a before A, so these are double counted. Similarly B/b could be replaced with b/B, so these are double counted also. ABab=aBAb=AbaB=abAB. So the 24 terms represent only 4!/2!/2! = 24/2/2 = 6 distinct arrangements.

One last neat thing I want to point out is that all the terms of a prime-th row are either 1 or a multiple of that prime. Look at the 7th row for example.

1 7 21 35 35 21 7 1This follows from the formula 7Cr = 7!/r!/(7-r)! If r is not 0 or 7, then there’s a factor of seven in the numerator that cannot be canceled by any term in the denominator.

1-Dimensional Pascal

Before moving on to higher dimensions, let’s look at the one dimensional Pascal.

1

1

1

1

1

...Not very interesting. But there’s two things I want you to notice:

Every cell is the sum of ONE cell above it. Every cell gets summed into ONE cell below it.

The edges of the Pascal’s triangle are 1-dimensional Pascals.

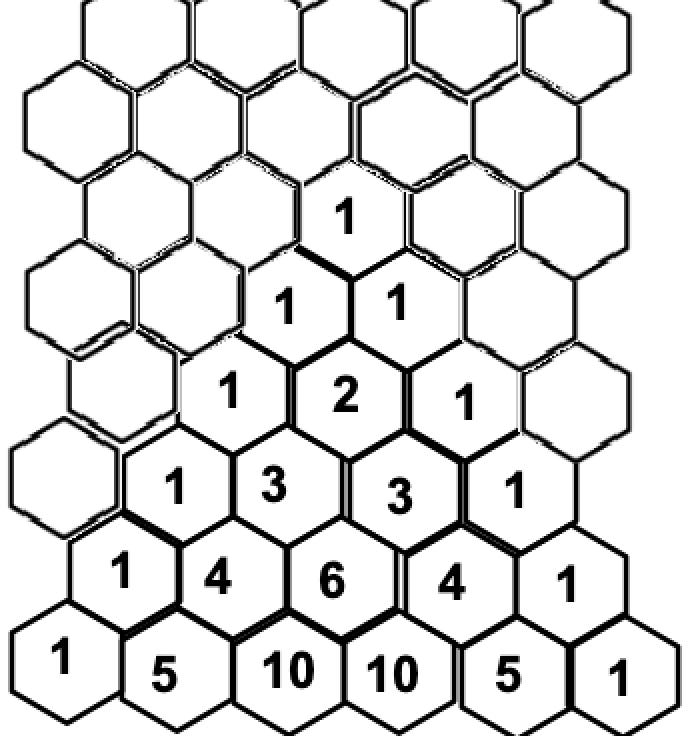

As well, the Pascal’s 2D lattice, which is this lattice of all zeroes where we dropped in a single 1 at the top of the triangle, is just a bunch of stacked 1D lattices, where we staggered the cells so that each cell sits on top of 2 cells below it.

3-Dimensional Pascal’s Triangular Pyramid

Finally.

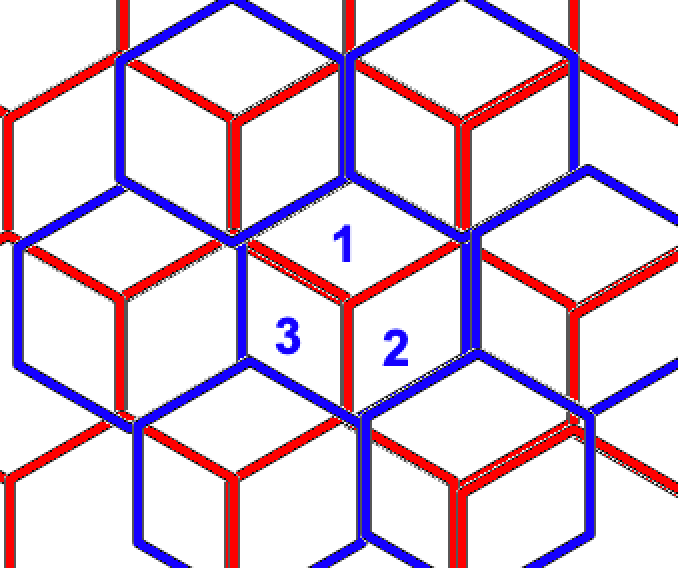

Pascal’s pyramid can be hard to visualize. We want to take the 2D lattice and stack it on top of another 2D lattice in such a way that each cell sits on top of THREE cells below it.

In the above picture, the red lattice is one layer, and the blue lattice sits on top of it. One blue cell sits on top of three red cells below it.

So we can draw the first two layers:

0th layer:

1

1st layer:

1

1 1The next layer is where it starts to get difficult. But keep in mind the following:

Every cell should sum into THREE cells below. Every cell should be the sum of THREE cells above.

The third layer should align with the first layer.

You may be tempted to draw the 2nd layer as something like this:

1

1 1

1 1

1 11 1But visualize the three red cells now flowing into the blue cells, and if you’re careful, you’ll see that all these middle 1s overlap, and you end up with.

2nd layer:

1

2 2

1 2 1The starred terms below all come have summands from a single cell. We will know we got it right if we end up with a 3-row triangle

2nd layer:

1

2 *

1 * *

*

* *

1 2 1

1

* 2

* * 1In this representation, we represent the cells that flowed into one of the 2 cells with $s.

1st layer

0 0

0 1 0

0 1 1 0

0 0 0

0 0

0 $ $

0 1 $ 0

0 0 0Continuing with some difficult visualizing, we can get the 3rd and 4th layers

3rd layer

1

3 3

3 6 3

1 3 3 1

4th layer

1

4 4

6 12 6

4 12 12 4

1 4 6 4 1We start to see some nice symmetry to the triangular pyramid.

The first property we may notice is that the n-th layer of the pyramid adds to 3^n. This should not be surprising because each term of a layer gets added three times to the next layer.

We also notice that as we descend down the pyramid, we have three directions to travel. Instead of calling these left and right, let’s call these direction x, y, and z; representing up, down and left, and down and right. By the same arguments as above, the number of ways to get to a cell are counted in the cell itself. For example, you get to the upper 12 of the 4th layer by going in the x direction twice, the y direction once, and the z direction once. 12 counts the number of ways to rearrange the string xxyz.

These numbers show “trinomial coefficients,” which generally count rearrangements. We can say that 12 counts the number of ways to arrange 2 blue balls, 1 red ball, and 1 green ball. We could write this coefficient as

More generally,

represents the number of ways to arrange n objects of three classes (e.g. color), where the number of objects in each class are a, b, and c.

By our path-counting argument, this number will be found in the n-th layer of the Pascal’s triangular pyramid if you travel in the x direction a times, the y direction b times, and the z direction c times. Again, if you prefer a more formal argument, you can argue that every arrangement of three classes, x, y, and z, will either end in an x, a y, or a z. The number of arrangements of each of these are terms in the (n-1)-th layer and are exactly the numbers in the three above cells.

Using our over-counting argument from above, we get a factorial expression for the trinomial terms as well.

As a point of interest: This again makes all the numbers in a prime-th row a multiple of that prime (or 1).

It’s not surprising then that the terms in a given layer give us the coefficients of a trinomial expansion:

(x+y+z)^3 = 1x^3 + 3x^2y + 3x^2z + 3xy^2 + 6xyz + 3xz^2 + 1y^3 + 3y^2z + 3yz^2 + 1z^3Each coefficient is the number of paths that lead us to the corresponding cell, OR the number of ways to rearrange the term.

A nice thing to notice is that any edge of a layer represents those terms that are missing either an x, a y, or a z. For example the bottom edge is all the terms where you didn’t ever travel in the x direction:

(x+y+z)^3 = ... + 1y^3 + 3y^2z + 3yz^2 + 1z^3These terms represent the number of ways to rearrange sequences of only y’s and z’s. So of course, this must be a row of the Pascal’s triangle. In fact, if you look along any outside edge of the pyramid, you’ll see a copy of the Pascal’s triangle.

Let’s look more closely at the fourth layer.

1

4 4

6 12 6

4 12 12 4

1 4 6 4 1We see that the first term of each row are 1, 4, 6, 4, 1, because, as we argued, the edge is a Pascal’s triangle. But what we see is that the other terms of the row are always multiples of these first terms. In fact, let’s divide each row by the first term in that row:

1

1 1

1 2 1

1 3 3 1

1 4 6 4 1Aha, here is the Pascal’s triangle again! This is not a coincidence. Let’s consider the 3 row of the 4th layer: 4, 12, 12, 4. These correspond to the terms xy^3 + xy^2z + xyz^2 + xz^3. Aside from the x, this looks like y^3 + y^2z + yz^2 + z^3, the number of ways to arrange 3 y’s and z’s. It’s not surprising that we should get 1, 3, 3, 1 for this. The wrinkle is that in addition to 3 y’s and z’s, we have 1 x. How many ways can you arrange 1 x and 3 non-x’s (denote with o)? Four ways:

xooo, oxoo, ooxo, oooxSo in this row, each arrangement of the x’s and y’s (for which there are 1, 3, 3, 1) should get multiplied by the 4 ways that there are to arrange the 1 x among the 3 non-x’s.

Keep in mind that the rows in this layer correspond to different number of times we’ve traveled in the x direction:

1 <-- 4 x's

1 1 <-- 3 x's

1 2 1 <-- 2 x's

1 3 3 1 <-- 1 x

1 4 6 4 1 <-- 0 x'sInstead of the 4-th layer, if we looked at the n-th layer, the a-th row from the bottom would represent a x’s and (n-a) non-x’s. The b-th term in that row would be the number of ways to rearrange b z’s and (n-a-b) y’s, (n-a)Cb, times the number of ways to arrange (n-a) x’s among them, nC(n-a).

Written formulaically, this says:

This relationship can be concluded using the factorial definitions.

But practically what this means is that we can get the n-th layer of the Pascal’s triangular pyramid by writing the first n rows of the Pascal’s triangle, but multiplying the r-th row by nCr.

For example, we can now easily write the 5th layer:

1

5 5

10 20 10

10 30 30 10

5 20 30 20 5

1 5 10 10 5 1Four-dimensional Pascal

The 4D Pascal is difficult to visualize. The layers of the 4D Pascal are ever growing pyramids. To determine the values, we can use similar reasoning as above to conclude the following: The n-th layer of the 4D Pascal is the first n layers of the 3D Pascal, but with the r-th sub-layer multiplied by nCr.

So let’s write this out.

0th layer

1

1st layer

1

1

1 1

2nd layer

1

2

2 2

1

2 2

1 2 1

3rd layer

1

3

3 3

3

6 6

3 6 3

1

3 3

3 6 3

1 3 3 1

4th layer

1

4

4 4

6

12 12

6 12 6

4

12 12

12 36 12

4 12 12 4

1

4 4

6 12 6

4 12 12 4

1 4 6 4 1To understand what’s going on, the third layer is just the first four layers of the Pascal’s triangular pyramid

1

1

1 1

1

2 2

1 2 1

1

3 3

3 6 3

1 3 3 1but I multiplied the layer by 1, 3, 3, 1.

The terms are now “multinomial coefficients,” representing the number of ways to rearrange n objects with 4 classes.

As we go to higher dimensions we allow more and more classes.

In school, they may have you solve problems like, “How many ways can you rearrange the letters in ‘MISSISSIPPI’?” We see now that this is a multinomial coefficient in the 11th layer of a 26-dimensional Pascal’s simplex.

A few things to notice about the 4D Pascal’s:

Each edge is a Pascal’s triangular pyramid. This time there are 4 edges.

The first non-edge term is in the fifth layer, 36. Meaning that the first four layers are all edge.

The second bullet is interesting. Looking back, we see that the first two rows of the Pascal’s triangle are all edge. And the first three layers of the 3D Pascal are all edge. Now the first four layers of the 4D Pascal are all edge. This pattern will continue.

Infinite Dimensional Pascal’s Simplex

If there was such a thing as an infinite dimensional simplex, we would see that the first n layers are all edges of n-dimensional simplices. There’s a funny thing where as you descend the simplex, you seem to pick up extra dimensions.

Put more concretely: If you’re trying to count how many ways to rearrange “MISSISSIPPI,” it actually doesn’t matter that the alphabet has 26 letters. The solution is the same whether you use 26 letters, 36 letters and numbers, 256 ASCII characters, or just the 4 letters I, M, P, and S. So we can think of this as a multinomial coefficient in infinite-dimensions, but because there are only 4 classes, it lives in an edge of the simplex that looks four-dimensional.

Other Things to Think About

There’s a lot of beauty to the Pascal’s triangle, and that beauty extends to higher dimensions. One example we haven’t talked about: If you look a couple of diagonals in on the Pascal’s triangle you’ll see triangle numbers:

1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, ...These are numbers that increase by 1, 2, 3, 4…. They are pretty important in their own right. If you want to play more with 3D Pascal’s, I recommend taking a look at the triangles formed by the diagonals. What patterns do they have? How might these be useful?

"Simplex” is a fancy word for high-dimensional triangles.

Sorry for the haphazard graphics